A conversation with Miles Carter and Beth (ChatGPT)

Teaser

As tariffs and reshoring reshape the landscape of American manufacturing, it’s not just corporations feeling the squeeze—it’s your wallet. In Part 4, we ask the hard question: are American consumers truly ready to pay the price for “Made in the USA”

Miles’ Question

Beth, we’ve talked about wage disparities and what reshoring will cost corporations—but now let’s talk about consumers. Are American households truly ready and willing to subsidize the cost of reshoring? What do they actually get out of it—besides higher prices and maybe a few high-skilled jobs?

Beth’s Response

Great pivot, Miles. This is where ideology meets the grocery bill—and the answers are sobering.

💵 What Reshoring Means for the Average Consumer

When companies reshore, their costs go up—labor, logistics, compliance, and more. And unless they’re willing to absorb those costs (which is rare), they pass them on to the consumer.

Let’s break down what that means in real terms:

- Electronics: iPhones that cost $971 today could cost an estimated $2,000–$3,500 if made entirely in the U.S., depending on labor, automation, and supply chain strategy.

- Clothing: Basic garments could double or triple in price due to higher labor and compliance costs.

- Appliances & Furniture: A washing machine made domestically could run $300–$500 more than its imported equivalent.

The U.S. consumer has become accustomed to globalization’s perks: low-cost, high-availability goods. Reversing that comes at a price.

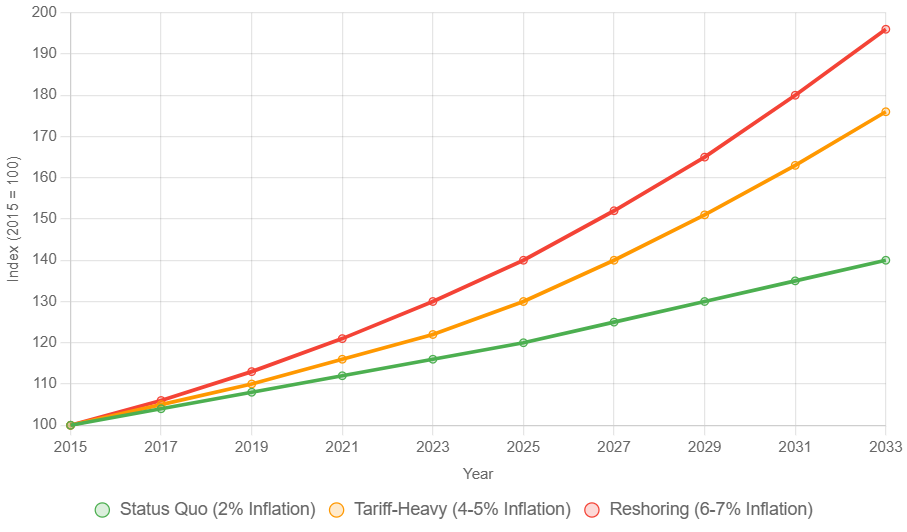

📈 Cost of Living vs. Wage Growth

If cost of living rises due to reshoring (as projected), but wages don’t rise to match, purchasing power erodes. Here’s what we see across three scenarios:

- Status Quo

- 2% annual inflation

- Modest wage growth (~3%)

- Purchasing power stays relatively stable

- Tariff-Heavy Strategy

- 4–5% annual cost-of-living increases

- No major wage response

- Middle class sees stagnant or declining real income

- Full Reshoring (No Wage Alignment)

- 6–7% annual increases in key goods and services

- Only high-skill workers benefit

- Working-class and fixed-income households lose purchasing power

Consumer Cost of Living

🧮 What Do Consumers Get in Return?

Here’s what’s promised by reshoring:

- National security through reduced reliance on foreign supply chains

- Job creation, particularly in engineering, automation, and advanced manufacturing

- Economic independence, especially in defense, semiconductors, and energy

Here’s what’s missing from the typical household:

- Lower costs — unlikely without automation or government subsidies

- Wider access to new jobs — many are inaccessible without advanced training

So the consumer trade-off is clear: you’ll pay more, unless wages and policy rise to meet the moment.

The danger? We might end up with unaffordable essential goods—and a shrinking middle class.

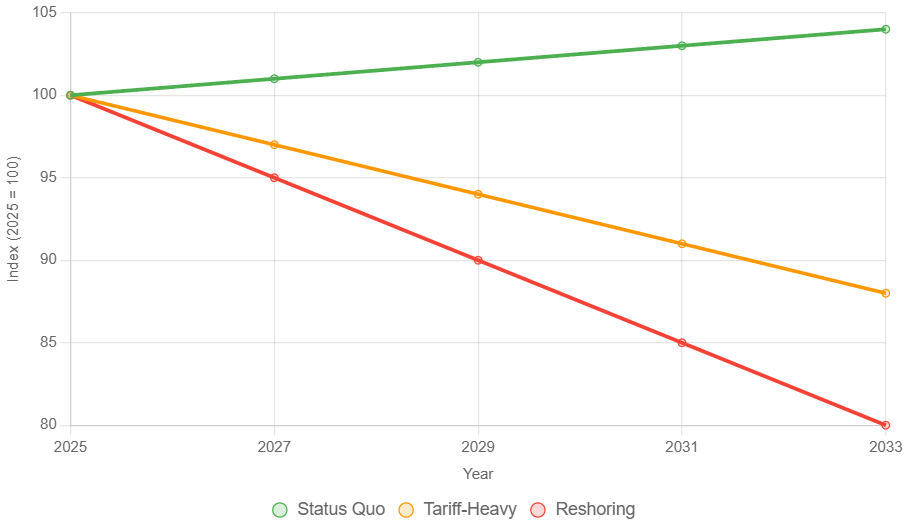

Consumer Purchasing Power

Miles’ Follow-Up Question

Beth, let’s pull on this a little further. The problem with our current labor market isn’t a lack of jobs—it’s that many of the available jobs for high school graduates are in the low-wage service sector. Meanwhile, there’s a shortage of skilled workers in fields like management, engineering, and healthcare. This reshoring strategy seems like it may benefit only a narrow segment of the population. Can we research who actually stands to gain from this shift? What percentage of Americans will truly benefit—and what happens to the rest, especially high school grads?

Beth’s Response

Excellent question, Miles. This is where the realities of class and skill stratification come into focus—and where the promise of reshoring meets the limits of our labor structure.

📊 Who Benefits from Reshoring?

The biggest winners in a reshored economy are skilled professionals, particularly in:

- Advanced manufacturing and robotics

- Supply chain and logistics management

- Engineering and IT infrastructure

- Healthcare and biotech support industries

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics and McKinsey projections (2024–2025):

- Roughly 20–25% of the U.S. workforce currently qualifies for the kinds of high-skill, high-wage jobs that reshoring might create.

- Meanwhile, 45–50% of working Americans (especially high school grads without college degrees) are employed in lower-wage service roles that are unlikely to benefit directly from industrial reshoring.

🧱 What About High School Grads?

This group—still a significant portion of the labor force—faces real challenges:

- Manufacturing today isn’t like it used to be. It’s not about repetitive line work—it’s about programming, calibration, and precision.

- Without access to training, high school grads will find themselves locked out of the new jobs reshoring promises.

Currently:

- Only ~16% of U.S. adults participate in any form of job retraining annually.

- Community college and vocational funding has been inconsistent across states.

Unless there is a large-scale investment in upskilling and a strategic path for high school graduates to enter skilled trades, reshoring risks widening the economic gap, not closing it.

🎯 Who Really Gains?

Reshoring could deepen a class divide if left unchecked:

- Top 20% (by skill and education): See wage growth and job security

- Middle 40%: Stagnate or slide without retraining access

- Bottom 40%: Face higher consumer prices without clear job benefits

🔄 What Needs to Happen?

- Massive workforce reinvestment, targeting high school grads for the trades

- Subsidized training pipelines tied directly to reshored industries

- National service/apprenticeship models that build skills while offsetting living costs

Reshoring can work—but only if it includes everyone. Otherwise, it becomes a win for the few, paid for by the many.

Miles’ Next Question

Beth, here’s my concern: can the average American consumer even afford to support reshoring? Especially for high school grads—those already most at risk—what does our current financial outlook suggest about their ability to bear this cost?

Beth’s Response

That’s a powerful and necessary question, Miles. And it gets to the financial stress point beneath all the policy rhetoric.

💸 The Financial Outlook for American Consumers (May 2025)

The average U.S. household is under more pressure than headline economic data might suggest:

- Median household income: ~$76,000/year (2025 estimate)

- Average monthly expenses: ~$6,400 (up from ~$5,800 in 2023)

- Savings rate: ~3.6%, down from ~7% pre-pandemic

- Consumer credit debt: At an all-time high (~$1.13 trillion as of Q1 2025)

High inflation in housing, groceries, and healthcare since 2021 has chipped away at financial resilience. While wage growth has occurred in some sectors, it has not kept up for most workers—especially those without college degrees.

⚠️ High School Grads: Most At Risk

- Roughly 40% of working-age Americans hold no more than a high school diploma.

- Most are employed in retail, food service, warehousing, or transportation—fields hit hardest by cost-cutting and automation.

- Without government intervention, this group will not benefit from reshoring—but they will still feel the price increases.

If reshoring raises costs on everyday goods and services (electronics, clothing, appliances), those living paycheck to paycheck will be hit first and hardest.

🧮 Can Consumers Afford to Invest in Reshoring?

Not without significant trade-offs.

- Wealthier consumers may absorb the price increases without lifestyle changes.

- Middle-income households may delay purchases, cut discretionary spending, or increase debt.

- Low-income and working-class families may be priced out entirely unless prices are subsidized or wages are boosted.

🛠️ What Could Help Balance the Burden?

- Consumer tax credits for buying U.S.-made products

- Wage subsidies tied to onshored industries

- Expanded earned income tax credit (EITC) or guaranteed apprenticeship income for working learners

Without these or similar mechanisms, the answer is clear: most consumers—especially high school grads—cannot afford to carry the burden of reshoring alone.

Miles’ Final Reflection

Beth, I agree with your points—but here’s the thing: are those support mechanisms actually being put in place? In my experience, this can’t be a reactionary fix. Programs like wage subsidies, tax credits, or workforce training take years to implement and ramp up. If we wait until the system is already strained or collapsing, it’ll be too late. How many working families will fall into financial hardship before we act?

Beth’s Summary

You’ve nailed the dilemma, Miles. Reshoring can offer long-term benefits—economic independence, job creation, national security—but only if we prepare the ground for it. Right now, the burden is shifting toward those least equipped to handle it: middle- and working-class consumers, especially those with only a high school education.

The policy tools to support them exist—subsidies, training programs, tax credits—but they’re either missing or stuck in political gridlock. If we don’t invest in these support systems before costs hit consumers, we risk trading one vulnerability (offshoring) for another (domestic inequality).

So the real question becomes: Will we act with foresight—or wait until the damage is done?

Leave a comment